- Home

- Brian Keene

Where We Live and Die Page 3

Where We Live and Die Read online

Page 3

Figuring it was my cat, Max (who lives outdoors and was the source of inspiration for Hannibal from my short story, “Halves”), I turned around and then stopped.

Ever see the wind pick up a bunch of leaves and spin them in a mini-cyclone? It’s common, of course. That’s what was happening. The leaves around the cross were spinning fast, reaching a height of about five and a half feet off the ground. Then, as quickly as it had started, the breeze died off and the leaves floated back down to the ground.

That was the first thing that happened. I didn’t think much about it at the time, and even now, I’m almost willing to chalk it up to nothing more than a natural occurrence—except for everything that’s happened since then.

In hindsight, there was nothing about it that was natural…

ENTRY 7:

The second thing that happened is also somewhat dubious, but when considered in the greater context, it makes me wonder, especially given her recent expressed desire to move.

Cassi is a smoker. Ever since the baby came along, she only smokes outside, and then, only after he’s gone to bed. There’s an ashtray out on the deck, along with a table, four chairs and the glider. Oh yes, we can’t forget about the porch glider. It’s the central part of our story.

The glider is a family heirloom. It belonged to Cassi’s grandmother and was given to us after she passed away. Cassi has fond memories of sitting on it when she was a little girl. It’s very comfortable, but the cushions are a garish, green floral print and when it rains, they soak up the moisture. Sit on them after a storm and your ass will get wet.

Within two days of the accident, Cassi stopped smoking out on the deck. Instead, she began smoking in our bathroom with the door closed and the exhaust fan running full blast. At first, I didn’t think anything of it. Keep in mind, it was winter. I just assumed that it was too cold outside to smoke. But as months passed and the nights grew warmer, she still avoided smoking out on the deck. When I asked her why, she said she got spooked out there at night. Neither our flashlight nor the big dusk-to-dawn light that’s installed on the side of the garage helped. She said it was still too dark out there, and sometimes, she felt like someone was watching her. Despite those lights, the top of our driveway remains pitch black at night. If you shine the flashlight up the hill, the beam gets lost in the darkness, almost as if the shadows are swallowing it. The only thing that dispels the darkness are the headlights of approaching cars, and then, only for an instant.

I asked her when she’d started feeling this way, and she said it was after the accident.

My wife is not given to flights of fancy. She’s firmly grounded in reality. She’s the Agent Scully to my Agent Mulder, to put it in terms of The X-Files. The only spiritual or supernatural activity she even remotely engages in is occasionally attending Catholic or Episcopalian church services. She doesn’t believe in aliens or Bigfoot or the Loch Ness Monster or ghosts. Despite this, being out on our deck and staring up at the driveway at night has made her uncomfortable enough to start smoking inside. As I write this, many months later, that is still her practice. Let’s call that occurrence number two, and catalog it accordingly.

ENTRY 8:

If this were a horror novel, I’d plot it like one, but it’s not a horror novel. It’s simply a diary, notating a random collection of occurrences, all of which have happened since the accident. I’m jumping around here. One minute, I’m in the present. The next, I’m back to the beginning again. There is no linear narrative. There is no slow build of suspense and dread. There is only me, trying to make sense of it all.

I can’t remember who said it, but there’s a great quote regarding The Amityville Horror, Poltergeist and similar haunted house stories. The quote (and I’m paraphrasing here) goes something like this: ‘If this stuff really happened, if the house was really haunted, then why did the people stay? Why didn’t they move the fuck out as soon as they heard the voices/saw the ghost/the dog started levitating? Because that’s what would happen in real life.’

Except that’s not true. I know, because this is real life. This is real fucking life and we can’t move. We can’t move because we can’t afford to move. We can’t afford to buy another house. Cassi’s been talking about it again—talking about finding a place with sidewalks and fenced-in backyards where the baby can play. A year ago, she was fine with him growing up playing in our big backyard with its trees and trout stream and wild outdoors. Now she’s craving suburbia, and I think I know why. I don’t think it has anything to do with sidewalks. It has to do with some of the things that have happened here.

That should make me happy, because if it’s true, then it means that I’m not crazy. If she’s experiencing things too—enough that she suddenly wants to move—then that’s proof right there that I’m not losing my mind. Right? If so, then I should be ecstatic. But I’m not. I’m not because this is my family we’re talking about, and we probably should move and I can’t afford to do it. I’m supposed to take care of them and provide for them and protect them, and in this case, the best way to do those things is to buy another house and get the hell away from here.

I wish sometimes that I still had a real job, a job where I operated a machine or moved boxes around, and got a paycheck every week for my efforts. A job with health insurance and a 401K would be nice, too. It would be awesome to have a job where people didn’t email me at the end of the day, after I busted my ass for eight hours, and say, “Your last book sucked. When are you gonna write another zombie novel?” But I’d even put up with that, as long as the job gave me a steady enough income that I could buy us a new home.

Earlier this week, I tried to get a job like that. I went back to two of my former employers—the foundry and the loading docks. Neither one of them were hiring, on account of the economy. The Human Resources Director at the foundry said, “You must be a millionaire from all those books. Why would you want to come back to work here?”

Life is nothing more than a series of lyrics from Bruce Springsteen songs.

This is good whiskey. Woodford Reserve. Big fucking bottle. I believe I will have some more. I believe, in fact, that I will drink this bottle dry tonight.

The people in those stories don’t move out because they can’t. They’re trapped.

So am I.

ENTRY 9:

The third bit of strangeness occurred around the end of March. In truth, I’d again forgotten all about the accident. Oh, sure, I thought of it for a second when I went up to get the mail or pulled in or out of my driveway. The cross was kind of hard to miss. The floral arrangements had since withered and died, but the marker was still there. So while I did occasionally think of the accident, such thoughts were fleeting. They weren’t even fully-formed thoughts. If anything, they were just echoes.

I’d even forgotten about the mini-cyclone the leaves had formed. Cassi had taken to smoking inside, but as I said earlier, I hadn’t put two and two together at that point, and didn’t know why she’d changed her routine. I thought it was because of the cold weather.

The third occurrence was an incredibly vivid and detailed dream. I know that I dream all night. I’ve been told by Cassi, ex-girlfriends, my ex-wife, one-night stands, cellmates, my old Navy buddies and anyone else who has ever slept beside me that I’m restless at night. I kick and twitch and talk in my sleep. Not mumbling. Not whispering. No, I have loud, boisterous and elaborate dream conversations. Sadly, I never remember them. It’s rare that I remember any of my dreams. But I remembered this one. It happened in March. Here we are, months later, and I still remember every detail.

In the dream, I was sitting out on our deck after dark, smoking a cigar and looking up at the stars twinkling down through the tree limbs. I do this quite a bit in the waking world, so the dream was pleasant enough. Max was sprawled in my lap, and I was petting him with one hand and holding my cigar in the other. My dog, Sam (who was the inspiration for Big Steve in my novel Dark Hollow, as well as many other things), was sprawled at my

feet. There was a glass of bourbon on the table in front of me. Crickets and spring peepers were chirping over in the swamp, and in the distance, I could hear the soft, muted roar of the trout stream. Eventually, I became aware that Max and I weren’t alone. I heard the glider rails squeak, as if someone was slowly rocking back and forth. I turned around and there was a girl sitting on the glider. As soon as I saw her, Max jumped down off my lap and ran away, hissing.

The girl was young, maybe eighteen or nineteen years old. She had long, shoulder-length blonde hair, combed straight. She was thin but not skinny. Pretty. She wore denim jeans, sneakers and a white t-shirt. She clutched a black cell phone in one hand, and held it at her side, as if waiting for it to ring. When she raised her head and looked at me, her expression was one of profound sadness.

She said something, but I couldn’t hear her. Her lips moved silently.

And then I woke up. I lay there for a while, thinking about the dream and wondering what it meant. Did I know the girl? She seemed vaguely familiar, but I didn’t know why. I was left with a sense—a certainty—that I should know her, and yet I didn’t. Who was she? Could she have been a fan I’d met at a book signing, perhaps? Or maybe someone I’d encountered briefly at some point in my life, but had since forgotten—an old coworker or one-night stand?

I didn’t know, and the harder I thought about it, the more important it seemed.

Unable to sleep, I slipped out of bed, pissed, and then put on my robe. I went out to my office, made a pot of coffee and worked until five o’clock in the morning, at which point I came in and waited for the baby to wake up. When he did, I got him out of the crib, changed his diaper and made him breakfast. When Cassi finally woke up, she was grateful for the opportunity to sleep in. She asked me what time I’d gotten up, and I told her. Then I told her about the dream. She agreed that it was odd.

A new day began, but unlike the leaf cyclone or the accident itself, I didn’t forget about the dream. I jotted it down in my commonplace book (a notebook that many authors use to write down story ideas, scraps of dialogue, plot devices, sketches, or anything else that occurs to them when they are away from their writing instruments) with the intent of cannibalizing it for a story at some point in the future. There was something about the dream. Something unsettling. I wanted to capture every detail. I needed to make sure that I would remember her face.

What I didn’t know at the time was that remembering her face wouldn’t be a problem for me, because I would see her again.

ENTRY 10:

About two weeks after that, I was sitting out on the deck with Sam and Max. It was early April, and quite a warm evening for the season. Much like in the dream, I was smoking a cigar, drinking bourbon and watching the stars. I even remember what brands the cigar and bourbon were—Partagas 1845 Black Label and Knob Creek with just a little bit of ice. Max was sprawled in my lap, all twenty pounds of him, purring and stretching and acting not at all like the badass outdoor tomcat he likes to portray himself as when others are around. Sam was lying at my feet, leash-free, but to keep him on the porch, I’d strategically placed two baby gates at each of the deck’s exits. Had I not done this, Sam would have waited until I was distracted and then dashed off into the woods. He is a mutt—mostly a mix of Rottweiler and Beagle, the latter of which comes out in him whenever he catches a scent. We walk quite often through the woods and whenever he sniffs a rabbit or a fox or any other creature, he strains at the leash hard enough to choke himself. On the few occasions where he’s actually slipped his collar, he runs off without thought of consequence, totally focused and consumed on tracking his quarry. Usually, he ends up lost and exhausted to the point of collapse, and I have to hunt him down and carry him back home. The baby gates prevented that, and allowed me to enjoy my cigar and whiskey in peace. Cassi was inside, talking on the phone to J. F. “Jesus” Gonzalez’s wife. The baby was asleep. All was right with the world.

I was sitting there smoking and thinking about literary estates. Jesus and I had both been wanting to create literary estates for our families. I was pretty sure that was what Cassi and her friend were discussing, as well, because in addition to the literary estates, we wanted to legally draft an agreement wherein if either Cassi and I or Jesus and his wife died unexpectedly, we would gain legal guardianship over the other’s children. Cassi was of a mind that we didn’t need to worry about things like that yet, but I wasn’t so sure. Both of our parents are too old to care full-time for a child, and my oldest son, who was eighteen at the time, had his whole life ahead of him. It didn’t seem right to burden him with the possibility of having to care for his younger half-brother, should something happen to us.

Creating a literary estate took money, something that neither Jesus nor I had much of. I’d gotten a sample draft from a link Neil Gaiman had posted, and was weighing the possibilities of finding something similar on LegalZoom.com or another website. I wondered if such a document would still be considered legal. This was important to me. I didn’t want to die and have the rights to my work fall into the hands of one of my publishers. The money, what little there was, should go to my sons.

This was what I was thinking about when Sam started growling. I glanced down at him. He was staring at the top of the driveway. His ears were flattened and his haunches were raised. His tail was between his legs and he stood stiff as a board. When I reached for him, he growled again. His eyes never left the spot at the top of the hill.

I looked around, thinking he’d seen an animal, but the driveway was deserted. Annoyed, I picked up Max, sat him down and then took Sam inside. When I came back out, Max had run off to the garage and was standing outside the door, meowing to be let in. Although he is an outdoor cat, Max sleeps in the garage at night. It provides him safety from the cold in the winter and protection from nocturnal predators like coyotes and foxes and owls in the warmer months. I opened the door and let him in. Then I closed it behind me and returned to my cigar.

As I sat down again, the porch glider began to move. The rocking was slow, but noticeable. Back and forth. Back and forth. The aluminum struts squeaked. Max began howling inside the garage. In the house, I heard Sam start growling again. He barked once, loud and powerful. Then Cassi hollered at him to shut up. Her voice was muted, almost lost beneath the forcefulness of his bark. Through it all, the glider kept rocking. There was no wind. I glanced up at the treetops to confirm this. No wind, not even a slight breeze. Sometimes, when a dump truck or tractor trailer goes barreling down the road, they’ll vibrate our deck, but the road was clear. There were no vibrations, no disturbance.

And yet the glider was moving.

I said, “What the fuck?”

The glider’s rails squeaked in response as it continued rocking. Cigar clenched between my teeth, I walked over to it. It stopped moving when I was halfway across the deck.

If this was fiction, this would be the part of the story where the protagonist starts to put two and two together—the dream of the girl on the glider (so eerily similar in setting to what was now occurring in real life), the glider moving on its own while the protagonist watches. But this isn’t fiction, and I didn’t put those two events together. Not then.

That came after my son started saying “Hi” to something I couldn’t see.

ENTRY 11:

Been a few days since I worked on this. Real life intruded. To paraphrase Bob Segar, deadlines and commitments, what to leave in and what to leave out. I finished the extra material for Darkness on the Edge of Town tonight. It’s a little after 3am and I’m sitting here wondering how “Bounce, Rock, Skate, Roll” by Vaughan Mason & Crew ended up in my iTunes library. I’ve got about ten-thousand songs on iTunes, the culmination of a lifelong music collection, and when I write, I put them on random shuffle. It makes for eclectic and inspiring background music. I never know what will pop up next. Jerry Reed and then Anthrax, followed by The Alan Parsons Project and then Marvin Gaye and then Public Enemy and then Johnny Cash or Guns N’ Roses or Neil

Diamond or Iron Maiden or Alice In Chains or Dr. Dre. But I don’t remember ever owning this disco tune, and here it is, blasting from my computer’s speakers and subwoofer.

I don’t have a lot in life. Material wealth has not accompanied my success, and these days, I seem to have more hangers-on and acquaintances than I do real friends, but the one thing I’ve got going for me is a kick-ass collection of tunes. And an awesome fucking library. This is what I leave behind for my sons—a metric fuck-ton of books, comics and music.

Anyway, I went back through this tonight, reading what I wrote, and I noticed something. Even in this, my secret diary, I avoid mentioning the baby’s name. When he was born, Cassi and I made a decision to guard his privacy as much as possible. We’ve never posted a picture of him online. Indeed, when I do talk about him in public, I refer to him as ‘Turtle,’ rather than his real name. Maybe we’re just being paranoid, but I don’t care. I’ve got enough crazies out there, and have gotten enough death threats that I’m not taking any chances. Like I said at the beginning, I genuinely half-expect to get done in by some crazed ‘fan’ one of these days. What’s to stop Nicky, the guy who said he wanted to, (quote) “shoot me in the head with a crossbow because I psychically stole his story ideas” (end quote) from hopping on a Greyhound and coming to York County and tracking down my kid at school? These are the thoughts that keep a horror writer awake at night. So we guard his identity, and I did it even here, in this Word document, and I wasn’t even aware I was doing it until now.

I would do anything for my sons. I would murder others to keep them safe. My oldest son, David, is now an adult and can fend for himself. He’s as big of a genre geek as I am, and he likes telling goth girls who his dad is, in hopes of getting laid. And it works, too. He gets more game at sci-fi and horror conventions than Coop and I ever did back in the day. I don’t have to worry about him as much anymore. He’s a smart kid…hell, he’s not even a kid. He’s a man, now. But I still have to worry about my youngest son. The world is a scary place and he has no fear. When he attempts to climb out of his crib, he isn’t aware that he might fall. When he clambers up onto the couch and rolls around, he doesn’t realize that he could tumble off. He is not afraid of the electrical outlets or the neighbor’s dog or the swift, deep and powerful stream running through our property. He has no fear of strangers. He greets everyone he meets by waving his little hand in the air, smiling broadly until his dimples overshadow the rest of his face, and then shouting “Hi.”

The Rising

The Rising Entombed

Entombed Take the Long Way Home

Take the Long Way Home Jacks Magic Beans

Jacks Magic Beans Ghost Walk

Ghost Walk An Occurrence in Crazy Bear Valley

An Occurrence in Crazy Bear Valley Darkness on the Edge of Town

Darkness on the Edge of Town Welcome to the Show: 17 Horror Stories – One Legendary Venue

Welcome to the Show: 17 Horror Stories – One Legendary Venue Blood on the Page: The Complete Short Fiction of Brian Keene, Volume 1

Blood on the Page: The Complete Short Fiction of Brian Keene, Volume 1 Pressure

Pressure A Gathering of Crows

A Gathering of Crows The Rising: Selected Scenes From the End of the World

The Rising: Selected Scenes From the End of the World King of the Bastards

King of the Bastards Tequila's Sunrise

Tequila's Sunrise All Dark, All the Time

All Dark, All the Time Where We Live and Die

Where We Live and Die The Complex

The Complex The Library of the Dead

The Library of the Dead The Conqueror Worms

The Conqueror Worms The Girl on the Glider

The Girl on the Glider Urban Gothic

Urban Gothic Kill Whitey

Kill Whitey Terminal

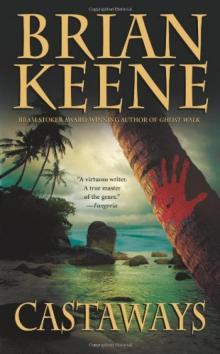

Terminal Castaways

Castaways