- Home

- Brian Keene

Ghost Walk

Ghost Walk Read online

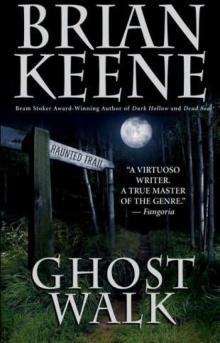

BRIAN KEENE

GHOST WALK

For Joe Branson and Dave Thomas,

until talking pirate cats fight a Yeti…

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Author's Note

Acknowledgments

Praise

Also By Brian Keene

Copyright

CHAPTER ONE

Mother Nature held her breath. The woods were quiet. There was no breeze to rustle the few leaves still clinging to the trees, or to toss around the fallen ones littering the forest floor. There were no crickets chirping. No locusts or bees buzzing. No mosquitoes or gnats. No birdsongs. Richard Henry couldn’t remember ever being in the woods and not hearing at least one bird. There were no squirrels either. Usually, if he stood still long enough, he’d hear them playing in the branches and chattering at one another—but not now. Back at the forest’s edge, near the dirt road where he’d parked, the woods had been alive with activity. He’d seen rabbits, insects, birds, squirrels, and even a mangy stray cat hunting a field mouse. But now there was nothing. Not even a pine cone or dead branch falling to the ground. Everything was still. Even the clouds in the sky, glimpsed between the treetops, remained motionless.

As if the forest was dead.

The silence felt like a solid thing; invisible walls pressed down on him.

Worse, something was out there. Watching him. Rich was sure of it. He felt eyes staring at him through the thick foliage, and the sensation made the hair on his arms bristle. He was nervous. Jumpy. His skin tingled. His mouth was dry and it was hard to swallow. Rich stuffed an unflavored Skoal Bandit in his bottom lip and tried to work up some spit. He cleared his throat. It sounded very loud. The wind briefly whistled through the trees, bringing more sound to the stillness. Shivering, Rich zipped his jacket up to his chin. When his saliva was running again, he spat onto a pile of dry leaves. Normally, Rich smoked, but lighting up a Winston out here would only give him away to the wildlife—if he ever found any, that was. Nothing warned off animals like cigarette smoke. That’s why he preferred the unflavored Skoal. Mint or wintergreen flavored would have also warned the animals off. He stuck the round tobacco can into the back pocket of his faded jeans, retrieved his .30-06 from the rock he’d propped it up against, and continued on his way, trying very hard to ignore that watchful sensation.

He felt like an idiot for being nervous.

People in York County told all kinds of stories about the forest, but that didn’t make them true. They were just legends. Bullshit folklore. LeHorn’s Hollow was supposed to be full of ghosts, demons, witches, Bigfoot, the Goat Man, and hellhounds—but none of those things existed in real life. In real life, there were other things to fear. In real life, Rich had to deal with things like terrorism and cancer scares and health insurance and bills. And his only son, Tyler, getting killed in a war that didn’t make any sense—a war that nobody seemed to care about anymore. At least not enough to get off their couches, turn off their televisions, and protest about it in the streets. His parents had protested Vietnam in the sixties. That’s how they’d met each other. Rich had a picture of his parents standing at the Mall in Washington D.C., wearing bell-bottoms, carrying placards, and flashing peace signs. His father had been in ’Nam the year before. He’d decided America shouldn’t be there and did what he thought was right. Came home after finishing his tour and added his voice to the dissent. Protested. Spoke up about things.

Rich’s generation—they’d dropped the ball. Nobody cared anymore. People didn’t give a shit about the war. As long as they had Paris Hilton and Britney Spears and George Clooney and Bran-ge-fucking-lina or whatever the hell they called themselves, that was all people cared about. Democrat or Republican—both were part of the problem, rather than a solution.

He’d lost Tyler. And as if that wasn’t enough, after his son’s death, life poured it on and turned up the heat. It was a mixed metaphor, but Rich didn’t give a shit. It was how he felt. Rich had to cope with getting laid off from the feed mill because they said his drinking was out of control. Said to clean himself up if he wanted to keep his job. What the hell did they know? Of course he drank. They would, too, if they had to put up with the shit he put up with. The government—the same government that was responsible for Tyler’s death—said he owed back taxes. And now the bank was threatening to foreclose on his home. They wanted their money and didn’t care if he was out on the street. The old house sat empty now, except for Rich; the other inhabitants would never return. Tyler was dead. The little bit of him that had made it home was buried in the Golgotha Lutheran Church cemetery; the rest was scattered across the sand. Rich’s ex-wife, Carol, was shacked up with another guy. A dentist. They lived in Windsor Hills with the rest of the yuppies. The only things that lived in the old place with Rich were the ghosts of his happiness.

The forest was haunted by the boogeyman? Bullshit. Terrorists and politicians and bankers and bosses and ex-wives and the pain he felt when he looked at Tyler’s pictures and remembered when he was so little—those things were the real boogeymen. Real life was scary as hell all by itself. Real life had enough monsters without adding make-believe monsters to it as well. Real life was a horror movie. Pretend monsters were an escape.

Rich had just turned forty-two, but he felt much older. Middle age had not agreed with him so far. It wasn’t the catastrophic loss of hair on top of his head or the coarse, gray hairs sprouting in places they had never been before—his ears and nose, shoulders and back. It wasn’t that he ran out of breath quicker these days. Or that he was tired all the time. Or that his head ached from the moment he woke up until he went to sleep. Or the extra weight around his waist, or his declining interest in sex and subsequently declining erections, or the way his back and joints hurt after doing simple tasks. He’d expected those things, had watched his own father suffer through them. They were all just part of the aging process. These things didn’t depress him, except when he was really drunk.

What got to him, what really brought him down, was how his life had seemed to disintegrate in the last few years. Ever since he’d turned forty, fate had delivered one kick in the balls after another. First there was Tyler’s death, then the divorce, a mountain of debt, and now the loss of his job and the foreclosure on the house. Everything kept falling apart and there seemed to be no end in sight. His days were one long, endless slide downward. It wasn’t fair. This was supposed to be the second half of his life, the path leading to the golden years, the twilight years. But sometimes Rich didn’t think he wanted to stick around for the second half. Things were supposed to get easier. When would that happen, exactly? It felt like things were just getting tougher instead. Could the golden years even be worth living?

He felt betrayed and alone.

Sometimes Rich just wanted to die. He imagined it was a lot like sleep. No cares. No worries. No pain. Just sweet, welcome oblivion, forever and ever—and if there was nothing after this, no Heaven or afterlife, he wouldn’t care anyway because he’d be dead.

Of cou

rse, if that happened, the family name would die with him. He had no siblings, no uncles with sons. Rich was the last male Henry from his father’s line. When Tyler had died two years ago in Iraq, a big part of Rich had died with him. The military had never revealed the whole story; just that Tyler had been riding in a convoy across the desert when a roadside bomb—an IED, the government man had called it—shredded his Humvee. One of Tyler’s friends, a kid from Mississippi, had died right away. Not Tyler. He’d lingered for almost fifteen minutes. At the memorial service, an American flag was draped over his closed casket. His high school graduation picture sat on top of it in a nice frame from the Hallmark store. In the picture, Tyler was smiling and whole. In the coffin, he wasn’t. The preacher talked about God and country and sacrifice. Then Tyler was buried.

The rest of the world moved on.

Rich did not.

Carol left him soon after. She said she’d been planning it for years, and had just wanted to wait until Tyler was grown and out of the house. She’d delayed her plans when he joined the army and went to Iraq. But now…

She never finished the last statement. She didn’t need to. Sometimes, things unsaid spoke louder than words.

Carol had left him everything—the car, the house, the dirty dishes in the sink, their empty bed, and a mountain of debt. The credit cards were at their maximum, and they still had five years’ worth of payments left on the house. Whether she’d done it out of pity or guilt or just an eagerness to be done with him, the end result was the same: she’d fucked him one last time before moving in with her dentist boyfriend. Here he was, one year later, unemployed, almost homeless, poaching deer out of season. All so he wouldn’t have to spend his meager unemployment check on groceries, and could instead hold off the bill collectors for another few weeks.

No wonder he fucking drank. “Out of control,” his boss said? Not yet. Maybe soon, though, if things didn’t get better—and if he had enough bullets…

Yeah, he could get out of control. Go postal. It would be so fucking easy.

Rich glanced back through the forest. There were no paths or trails. No wide spaces or clearings. This part of the woods had been unscathed by the big forest fire of 2006. Here the trees grew close together, and the rocky soil was covered with dead leaves and twigs. As dense as it was, he was surprised to see thick clusters of late-season undergrowth thrusting up from the ground: fragile ferns, poison ivy, Queen Anne’s lace, milkweed, blackberries and raspberries, snake grass, pine and oak seedlings dotted the landscape. All of it would be dead in another week or so. Already, the leaves were turning brown. He couldn’t see more than fifteen feet into the foliage, but that sense of being watched remained. It gave him the creeps.

Probably a deer, he thought. Come on out here and let me put some punkinballs in you, sucker.

That would be nice. Bag a good-sized buck, field dress it, and haul the carcass back to the truck. Then hide it beneath the tarp and head home. Move it from the truck bed and into the garage without any of the neighbors seeing (Trey Barker, who lived next door, would call the game warden if he knew Rich was poaching). With luck, he could have it strung up, butchered and in the freezer before dark, and he would then have the entire evening to drink a few beers and watch whatever was on the tube. Maybe he wouldn’t even cry tonight when he went to bed. That would be an excellent change of pace from his normal routine.

He’d parked on the side of one of the old dirt logging roads. Rich wasn’t worried about someone spotting his truck. He was way off the beaten path, hunting along the border of the state game lands. If a game warden or someone else happened to drive by, they’d just as easily assume the truck belonged to a hiker or a fisherman or somebody digging up ginseng roots as they would a poacher. They might even think it was broken down or abandoned. As long as he was careful when he dragged the deer’s carcass out, he’d be fine.

Of course, first he had to shoot one. Hell, shoot anything, something.

But there was nothing.

It was late October—almost Halloween. Small-game season had just ended and deer season was still a month away. The only thing he could legally shoot right now were coyotes and crows, but eating a coyote was like eating a dog and crows didn’t have enough meat on them—and what little meat they did have tasted like shit.

But even the crows were absent today.

Rich wondered if he’d have had better luck coming in from the Shrewsbury side of the woods. Maybe so. He hadn’t come in that way because the volunteers from the fire department and other civic groups were busy working on their Ghost Walk—a haunted attraction that would open Halloween eve and run until the first weekend in November. Even though it was the first one, the organizers had said they expected thousands of people over the next month, ferried back and forth on hay wagons, walking the trail through the forest while people in masks jumped out and scared them. It only took up a small section of the woods, but there were a lot of people working there currently, and he couldn’t risk anyone spotting him poaching.

He spat tobacco juice again and listened to the silence. Then he walked on. As he wound his way through the trees, he reconsidered his skepticism. He could understand why people told ghost stories about this area. This far in, the woods had atmosphere. The stillness was unsettling. He wondered what it meant. Did the wildlife know there was a predator in their midst? He’d been quiet, had walked lightly, dipped instead of smoked, made sure not to wear any deodorant. He’d even worn dirty clothes rather than clean ones that would smell like detergent. But nothing was out there.

Well, almost. Something was out there. He just didn’t know what it was.

He felt those invisible eyes boring into him again, right between his shoulder blades. When Rich wheeled around, there was nothing there but trees and foliage.

“Come on,” he whispered. “Give me a rabbit. A pheasant or squirrel—anything, goddamn it.”

He was smack-dab in the middle of over thirty square miles of protected Pennsylvanian woodland, zoned to prevent farmers and realtors from cutting it all down and planting crops or building housing developments and strip malls. The pulpwood company and paper mill in nearby Spring Grove had logged a great swath of the forest in years past, but lawmakers, the raging forest fire, and the rising availability of cheaper paper from China had put a stop to that. The old logging roads still existed, however. They were rutted and washed out in some places, but even so, they still provided access to the deeper parts of the forest. The adjoining land on the outskirts of the woods that hadn’t been ravaged by the fire was zoned agricultural and filled with corn, strawberry, and soybean fields. Other outlying areas housed hunting cabins. Beyond the farms and hunting cabins were the small towns of Shrewsbury, Seven Valleys, Jefferson, New Freedom, Spring Grove, Glen Rock, and New Salem. York County’s heartland.

Rich had grown up in Seven Valleys, and other than a four-year stint in the Marines during the early eighties, and a vacation trip to New York City when Tyler was ten, he’d spent his whole life there. Rich had been in these woods thousands of times, but he’d never gone farther than he had today. With the game non existent, he forgot about the unseen presence spying on him and pressed on, ignoring that creepy feeling and venturing into areas he’d never seen before. He wasn’t worried about getting lost. He had his compass and he’d be able to find the road and his truck again. His only concern was not finding some meat in time to get home and watch some TV. He wished now that he’d shot something when he had the chance, closer to the road where he’d parked. At the time, he hadn’t wanted to risk somebody hearing him. But it appeared that all the wildlife had gone deeper into the forest, so Rich did, too.

This close to the center, the woods seemed lifeless.

And that damned sensation of being watched didn’t go away.

The distant drone of a chainsaw broke the silence, and Rich jumped at the sudden sound. The buzz ceased, and was followed by pounding hammers. Rich shrugged. Probably the volunteers from the fire departm

ent, building something for the Ghost Walk. It occurred to him that maybe that was why the game was so scarce. Maybe all the noise had scared the wildlife away. He hadn’t realized that he was so close to the haunted attraction’s location. Grumbling to himself, Rich pushed through the foliage and moved on.

A few minutes later, he came across the first of the dead trees. Soon, the tangled undergrowth cleared, replaced with a vast swath of desolate, barren ground. He was nearing what had once been the true heart of the forest: a burned and blackened area known as LeHorn’s Hollow, named after the farmer who’d once owned it. The big forest fire in the spring of 2006 had destroyed over five hundred acres of woodlands and totally eradicated the entire hollow. Several people died in the inferno. Investigators suspected arson or perhaps an accidental blaze, but they were never able to determine the exact cause. In the end, it was speculated that a careless cigarette or an untended campfire had sparked the conflagration. The event made national headlines. CNN and FOX News even sent reporters out to cover it. For five minutes, York County, Pennsylvania, was in the news for something other than the Intelligent Design versus Evolution court case.

A lot of Rich’s friends and coworkers had been relieved to see LeHorn’s Hollow burn down. It had been the main source of most of the ghost stories and legends associated with the forest, including a violent murder in the eighties, a series of cult-related killings in 2006 (right before the fire), and whispers of everything from witchcraft and devil worship to crop circles and flying saucers. Then there was the more recent legend of a Bigfoot-like creature called the Goat Man who was said to haunt the area. All of it was bullshit, of course, but standing here among the burned-out tree skeletons, with no breeze blowing and no sound or movement, and that per sistent feeling of being watched—Rich could understand how folks would believe the old tales.

His stomach grumbled. His tobacco tasted sour, so he spat it out and then put a new dip in. Rich checked his watch and sighed. Then he pressed forward. Burned tree limbs disintegrated beneath his feet. A splintered log crumbled into charred bits as he clambered over it. With each step, ashes and dust shot up into the air, swirling around him and clinging to his jeans and boots. It was like walking through black baby powder. He wondered why the vegetation hadn’t started to come back yet. There should have been green shoots and fragile saplings thrusting upward from the soil. He shrugged. Probably because it was so late in the year. Next spring might bring it back to life. Maybe the lack of new growth to forage on explained why the hollow was empty of wild game. The surface was devoid of any tracks or footprints, except for his.

The Rising

The Rising Entombed

Entombed Take the Long Way Home

Take the Long Way Home Jacks Magic Beans

Jacks Magic Beans Ghost Walk

Ghost Walk An Occurrence in Crazy Bear Valley

An Occurrence in Crazy Bear Valley Darkness on the Edge of Town

Darkness on the Edge of Town Welcome to the Show: 17 Horror Stories – One Legendary Venue

Welcome to the Show: 17 Horror Stories – One Legendary Venue Blood on the Page: The Complete Short Fiction of Brian Keene, Volume 1

Blood on the Page: The Complete Short Fiction of Brian Keene, Volume 1 Pressure

Pressure A Gathering of Crows

A Gathering of Crows The Rising: Selected Scenes From the End of the World

The Rising: Selected Scenes From the End of the World King of the Bastards

King of the Bastards Tequila's Sunrise

Tequila's Sunrise All Dark, All the Time

All Dark, All the Time Where We Live and Die

Where We Live and Die The Complex

The Complex The Library of the Dead

The Library of the Dead The Conqueror Worms

The Conqueror Worms The Girl on the Glider

The Girl on the Glider Urban Gothic

Urban Gothic Kill Whitey

Kill Whitey Terminal

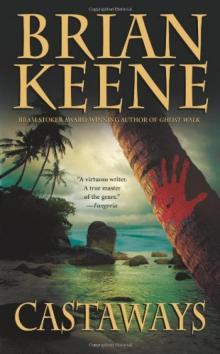

Terminal Castaways

Castaways