- Home

- Brian Keene

The Conqueror Worms Page 3

The Conqueror Worms Read online

Page 3

A moment later that chirp of victory turned into a frightened squawk, and the robin shot up into the air, his wings buzzing furiously. Something squirmed through the mud, and then burst upward after him.

I shouted from the window, wanting to warn the robin, even though he’d already seen it. The thing on the ground was hard to see amidst the rain and fog. I caught a glimpse of something long and brownishwhite. It was fast. It stretched toward the fleeing bird, and then there was empty air where the robin had been a second before.

The thing snapped back to the ground, like one of those Slinky toys my grandkids used to play with when they were little. A second later, it was gone as well, disappearing back down into the mud as if it had never been there at all.

Stunned, I closed the blinds and stood there, my hands and legs shaking in shock and disbelief. After a bit, I put my teeth in and made my way into the living room. Blue darkness had given way to the dim gray haze of dawn.

I stared at the cold and useless fireplace. I’d closed the chimney flue to keep the damp air out. It was built to keep the rain from coming in, but there was so much moisture in the air everything in the house ended up mildewed if I left it open. Above the fireplace was a mantle, made out of a wooden crossbeam taken from my daddy’s barn. It was old, like me. Also like me, it had survived numerous tornadoes and storms and hail and lightning and fires and droughts…and floods. Many, many floods.

On the mantle, my family stared back at me from their frames. I lost myself in them, trying not to contemplate what I’d just seen. Rose and I on our wedding day, and the portrait we’d gotten taken at the Wal-Mart in Lewisburg for our fiftieth wedding anniversary. She was even prettier in the second picture than in the first, taken a half-century before. Our kids: Tracy and Doug, when they were little. Next to that were snapshots of Tracy on her wedding day, her long, white veil spread out behind her on the grass, and another picture of her with her husband, Scott, taken on their honeymoon. Next to that was a photo of Doug taken in 1967, wearing his green beret, a First Cavalry patch emblazoned proudly upon his arm, just before he’d left for Vietnam.

There were no more pictures of Doug after that. That had been the last one, and I still remember the day Rose took it. I’d told Doug I loved him and that I was proud of him. He’d told me the same.

That was the last time we ever saw him. When he returned home, it was in a mostly empty coffin. The Viet Cong didn’t leave us much to bury.

There were more pictures of Tracy and Scott, Rose and myself, my best friend Carl Seaton and me with the sixteen-pound catfish we’d pulled out of the Greenbrier River eleven years ago, and the two of us standing next to the eighteen-point buck that Carl had shot one winter before old age stopped us from deer hunting altogether. Another showed me shaking the hand of our state senator while he gave me an award for being a World War Two veteran who’d lived long enough to tell about it. More numerous than any of these, though, were the pictures of my grandkids: Darla, Timothy, and Boyd.

All of them were probably dead by now, which was something that I’d been trying hard to avoid thinking about. Now it was starting to creep back in, because thinking about their likely deaths was better than thinking about what I’d just seen outside.

I got out a box of wooden matches and lit the kerosene heater. Its soft glow filled the room. I cracked the window just a hair—enough to let out the fumes, but not to let in the rain. Then I put the tin kettle on top of the heater and set the water to boiling, so I could have my instant coffee, which also was running low. My hands were trembling, partly from the arthritis and partly from the craving for some Skoal, but mostly from fear.

Although I didn’t want to, I thought about what I’d just witnessed.

The bird. It—

Rose had died of pneumonia three winters ago, quietly fading away in her hospital room in Beckley while I was down in the commissary getting a cup of coffee. Although I’d loved her with all my heart, for some time after she died, I was angry with her. Angered that she hadn’t said good-bye. That she went before me, leaving me here to fend for myself without her by my side. Rose had always done the cooking and cleaning and laundry, not because I’m some kind of male chauvinist, but because she’d truly enjoyed it. I was clueless—helpless—after her death. I didn’t clean the house for over a month. Tried to fry up some bacon and set off every smoke alarm in the house. The first time I tried to do laundry, I poured in half a bottle of detergent and flooded the basement with bubbles. Then I leaned against the dryer and cried for a good twenty minutes while the bubbles disintegrated all around me.

After that, Tracy and Scott pleaded with me to move up to Pennsylvania and live with them. Their own kids had moved out by then, leaving enough room for an old man like me. Darla was going to Penn State, studying pharmaceuticals. Timothy had moved to Rochester, New York, and was working with computers. And Boyd—well, he had joined the Air Force, just like his grandpa.

Just like me. Boy, that made me proud. He wanted to fly.

The bird. It tried to fly, and then—

The teakettle whistled, startling me. I poured hot water into my mug and spooned in some coffee crystals. I couldn’t stop my hands from shaking.

What in the world was that thing? It looked like a—

Instinctively, I knew my family was dead. I can’t explain it to you, other than to say that if you’ve ever felt that too, then you know exactly what I’m talking about. I just knew they were gone—a horrible, gutwrenching feeling. With Boyd, it was more than just intuition, though. Early on, before the storms hit America, I saw the coverage of the tidal waves that took out Japan. He was based there.

Now he was stationed at the bottom of the newly enlarged Pacific Ocean, and there’d be no more Japanese radios or cars or televisions or cartoon programs for a long while.

With the other members of my family, it was just a sense of knowing, a knot of tense certainty that settled in my stomach and refused to let go. It was like having a peach pit get stuck in your throat.

It’s a terrible thing to outlive your spouse. But it’s even more horrible to outlive your children and your grandchildren. A parent should never live longer than their child. The pain is indescribable. As I said earlier, I tried not to think about it. And yet, on the morning of Day Forty-one, I kept it fresh in my mind, picking off the scabs and letting the wounds bleed. I had to.

It was the only way I could stop thinking about what happened to the robin…

And the other thing. The thing that ate the bird. It had looked like a worm, except that no worm could ever grow that big. That was impossible.

Of course, so was the weather we were having. And I was too old not to suspend disbelief, especially when I’d seen it with my own eyes.

Could I trust those eyes? I wondered about that. What if the worm wasn’t real, that I’d hallucinated it? Maybe my mind was slipping. That scared me. For someone my age, dementia is much more terrifying than giant worms.

I sat there in the dim light, sipping instant coffee from a dirty mug and craving a dip. Cool air blew in through the slip of open window. Outside, the rain continued to fall. The fog rolled in and then lifted, then drifted back in again.

I stayed there all morning. Most of my days went like that, actually. There wasn’t much else to do. Occasionally, I tried the battery-operated radio, but the empty static always made me uneasy, so I’d snap it off again. Never had good radio reception back here in the mountains. The weather just made it worse, like in the truck on my ill-fated trip to Renick. The AM station in Roanoke had stayed on the air until about the fourth week. Mark Berlitz, the station’s resident conspiracy theorist and far-right talk radio host, had kept a lone vigil next to his microphone. I’ll admit that I listened in a sort of dreadful fascination as Berlitz’s sanity slowly crumbled from cabin fever. His final broadcast ended with a gunshot in the middle of “Big Balls In Cow-Town,” an old bluegrass song by the Texas Playboys (a shame, as I’d always enjoyed their music). The s

ong ended two minutes later, then there was silence. As far as I knew, I was the only listener to hear the disc jockey’s suicide, except for maybe crazy Earl Harper, who listened to the show on a regular basis and called in to it about every night.

I’d considered suicide as an option myself after that, but soon ruled it out. Not only was it a sin, but I also doubted I’d actually have the courage to go through with it. Certainly, there was no way on earth I could put one of the deer rifles in my mouth and pull the trigger. And I was afraid if I tried to overdose on painkillers, I’d end up paralyzed or something—paralyzed but very much alive. The thought of lying there, unable to move, and just listening to the rain was enough to convince me not to try it. But I thought about it again that morning, before dismissing the idea once more.

The morning went on and the rain continued to fall. I fooled around with one of the crossword puzzle books the kids got me last Christmas. When you get to be my age, your kin are clueless as to what to buy you for Christmas and your birthday. Since I liked crossword puzzles, that’s what they decided on. I was fine with that. It sure beat another sweater or a pair of socks.

I gummed the eraser on my pencil for half an hour, then put my teeth back in and gnawed on it, all the while trying to think of a three-letter word for peccadillo. I knew from four across, that it had an “i” as the middle letter, but I was damned if I could figure out what it was.

The coffee was bitter, and I wished for some green tea instead. Then, I sat up so suddenly that the crossword puzzle book fell to the floor.

Tea. Teaberry leaves! I’d known folks who’d quit dipping by chewing on teaberry leaves instead. It grew all over West Virginia, and I’d often picked the red teaberries growing in the woods behind my home, down in the hollow.

Cursing myself for not thinking about it sooner, I got into my rain gear and stepped out onto the back porch. The kitchen had two doors—one that led outside to the carport, and the other, which went out to the back porch. Since the back porch was closer to the edge of the forest, I went out that way.

Maybe if I had chosen the other door, and seen what was on the carport, things might have turned out differently later. Maybe I wouldn’t be writing this.

But I doubt it. I’d forgotten all about the robin at that point. The only thing my mind was focused on was the thought of finding some teaberry leaves to chew on.

I slopped through the yard. My breath clouded the air in front of me, and within minutes, my fingers and ears were cold. The fog had decided to stick around for a while. It covered everything. I could see for maybe fifteen or twenty feet, but after that, everything was concealed by white mist.

It was slow going, partly because of the weather, mostly because of my age; but I reached the edge of the forest and stepped into the trees. Under the leafy canopy, the vegetation was in better shape; the trees protected it from the constantly battering downpour. The rain beat at the treetops and dripped down on me. Wet leaves and pine needles stuck to my boots, and I went extra slow so I wouldn’t slip. It wouldn’t do to lie out here in the woods with a broken hip.

A few of the trees had been uprooted, but most still stood firm, their roots desperately clinging to the spongy ground. I noticed several of them had a strange white fungus growing on their trunks like the stuff I’d seen growing on the robin earlier. It wasn’t moss, at least not any kind I had ever seen growing on a tree. It looked more like mold, hairy and fuzzy and somehow unhealthy, sinister even.

Sinister, I thought. How can a fungus be sinister, Teddy? This nicotine withdrawal is eating away at what’s left of your mind. You’re losing it, old man. First you imagine that you saw a worm eat a bird, and now you think the moss is an evil life form bent on taking over the planet, like in a science fiction movie.

There was more of it on the forest floor, clinging to rocks, fallen logs, vines, and even the dead leaves and needles covering the ground. I was careful not to step in any of it.

Despite the havoc the weather was playing with the vegetation, I found plenty of teaberry plants growing up through the leaves on the forest floor. I knelt down to pick some, avoiding any that had that same odd fungus growing on them. As I collected the leaves, a twig snapped. City folks would have noticed that right away, but when you’ve spent as much time in the woods as I have, you don’t pay attention to every little sound the forest makes. You’ve heard it all before and know how to separate something odd and out of place from the rest of the forest’s symphony.

It wasn’t until there was a succession of snaps behind me that I turned. And stared.

My breath caught in my throat and the bottom of my stomach fell away.

A deer stood watching me from about twenty feet away; a spike buck, probably two or three years old. Water dripped from his antlers. He showed no fear or hunger, only curiosity. He looked half-starved, and his ribs showed through his wet, slick hide. But that wasn’t why I gawked at him.

The buck’s legs were covered with the same white fuzz that was on the trees. The stuff was spreading in patches along his belly and up onto his chest. It looked like it had fused with the deer’s body, eating through fur and flesh.

Stunned, I rocked slightly backward on the balls of my feet, and like a rifle shot, the deer leaped over a log and sped away, churning up leaves and twigs. As he fled, I noticed that his hind end was covered with the mold as well. Revolted, I hacked up a wad of phlegm and spat it on the ground. Then I made sure that I didn’t have any of the fungus on my skin or clothes.

I dropped the teaberry leaves back onto the ground. Whatever the fungus was, if it could spread from plant to animal, then I could probably get it from chewing the leaves in place of tobacco. I couldn’t be sure they weren’t already infected, so I scrapped the entire idea and slowly started home.

Behind me, from somewhere inside the fog, I heard another twig break. I paid it no mind, figuring it was just the buck again. But then I heard something else that definitely wasn’t a deer. A hissing noise, like the wind whistling through a partially open car window. I wheeled around and peered into the swirling mist, but there was nothing there.

Just the wind, I thought. Just the wind, whistling through the trees.

Then the wind crashed through the underbrush, sounding like a herd of trampling elephants.

After that, I hurried back to the house. At first the noise hurtled after me, but then it failed again. The memory of what happened to the robin dogged my every step. Occasionally, I stopped and listened, trying to determine if whatever was making the noise was following me. It was hard to hear it above the drumming rainfall. Something stirred beyond my line of site, but I never saw what it was—just a brown flash. At one point, I thought I felt the ground move, but I chalked it up to my imagination.

If I only knew then what I know now…

Back inside the house, I took off my wet clothes and collapsed into my easy chair. Just walking down to the woods and back had tired me out. Used to be I walked those valleys and ridges from before dawn until sundown, hunting and fishing andjust enjoying the outdoors. But those days were gone, vanished with the sunlight.

Exhausted and lulled by the soft sound of the rain, I closed my eyes and fell asleep in the chair. I dreamed about Rose’s blueberry pie.

The rain never slowed. While I slept, the wind had increased, and I woke up to the sound of a strong gust battering the side of the house. It was like the raindrops were being shot from the barrel of a machine gun. Reminded me of the war, in a way. It sounded like a hailstorm outside. I got up, looked out the big picture window, and couldn’t see more than a foot away from the house. The rain was coming down so hard now that it was like looking through a granite wall.

The wind blew the rain away from the house for a brief moment. I stared into the downpour; then I jumped back from the window.

Movement.

Something had moved out there. Something big. Bigger than the thing I’d seen earlier. And it had been close to the house. Between the clothesline an

d the shed.

Cautiously, I peeked outside again. There was nothing there. I chalked it up to old man jitters. Probably just a deer or even a shadow from a cloud.

I reminded myself there couldn’t be a shadow since there wasn’t any sunlight, and then I promptly told myself to shut up. Myself agreed with me. Myself then told myself that I was just a little skittish over what I’d seen happen to the bird earlier, or what I thought I’d seen. Add to that the white fungus growing on the deer and the trees, and the fact that I still didn’t have any dip, and I was bound to be a mite jumpy.

I sat back down and returned to the crossword puzzle book.

Three letter word for peccadillo, with an “i” in the middle…Three letter word…“i”…

“Oh, the hell with it!”

Exasperated, I threw the crossword puzzle book down and picked up Rose’s Bible instead. It was worn and tattered and held together with yellowed scraps of Scotch tape. It had been her mother’s and her grand-mother’s before that. I read it each day, taking ten minutes for a devotional. Like waking up at five in the morning, it was another one of life’s habits I couldn’t change, not that I’d have dared. Even with Rose gone, I knew that if I skipped a Bible lesson, I’d feel her watching me reproachfully for the rest of the day. I had no doubt in my mind she checked up on me from her place in Heaven. I opened the Bible. Reading it was like being with her again. Rose’s handwriting filled the book, places where she’d marked passages with a highlighter and jotted notes for the Bible study group she’d led every Wednesday night at the church.

A pink construction paper bookmark proclaiming For Mr. Garnett in a child’s crayon scrawl (a gift from the Renick Presbyterian Sunday School class) marked where I left off the day before, the Book of Job, chapter fourteen, verse eleven.

The Rising

The Rising Entombed

Entombed Take the Long Way Home

Take the Long Way Home Jacks Magic Beans

Jacks Magic Beans Ghost Walk

Ghost Walk An Occurrence in Crazy Bear Valley

An Occurrence in Crazy Bear Valley Darkness on the Edge of Town

Darkness on the Edge of Town Welcome to the Show: 17 Horror Stories – One Legendary Venue

Welcome to the Show: 17 Horror Stories – One Legendary Venue Blood on the Page: The Complete Short Fiction of Brian Keene, Volume 1

Blood on the Page: The Complete Short Fiction of Brian Keene, Volume 1 Pressure

Pressure A Gathering of Crows

A Gathering of Crows The Rising: Selected Scenes From the End of the World

The Rising: Selected Scenes From the End of the World King of the Bastards

King of the Bastards Tequila's Sunrise

Tequila's Sunrise All Dark, All the Time

All Dark, All the Time Where We Live and Die

Where We Live and Die The Complex

The Complex The Library of the Dead

The Library of the Dead The Conqueror Worms

The Conqueror Worms The Girl on the Glider

The Girl on the Glider Urban Gothic

Urban Gothic Kill Whitey

Kill Whitey Terminal

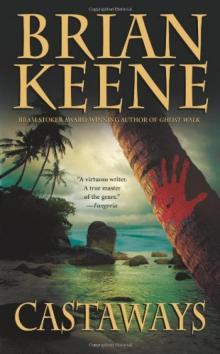

Terminal Castaways

Castaways